Scoot’d through the first hundred or so pages of Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude. Spaldeen, play’d in the Brooklyn streets with a pink-color’d rubber ball. Is that a bastardization of Spalding? The ball manufactory? The way Seeburg juke boxes in the south got call’d Seabirds?

Peter Gizzi

Oobleck, a Suess goo. Relationship to o.blek, a journal of the language arts?(Was it Ken Fifer, whose house in Bethlehem, Pa. burn’d down, who wrote a poem call’d “Me Being Stupid”? I always rather liked that.)

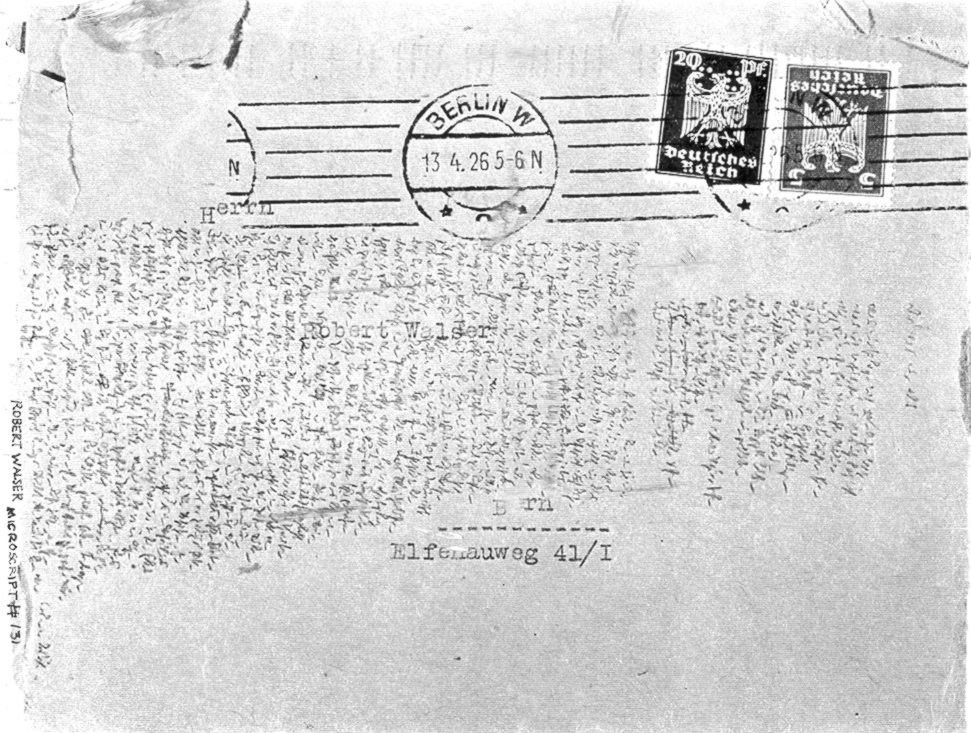

Poking around in a newish Robert Walser thing, Speaking to the Rose: Writings, 1912-1932, translated by Christopher Middleton. Which includes “fourteen translations from what has come to be called the ‘pencil area,’ or ‘Bleistiftgebiet.’

“The ‘pencil area’ was for a long time thought to be a corpus hermeticum, closed to the mortal mind because composed in an entirely private cipher. It was by matching certain strips of script to extant published texts that Jochen Greven first showed that the cipher had been all along an adroitly, if most idiosyncratically, abbreviated script. The 526 packages of this writing now fill 2,000 pages in the six volumes of Aus dem Bleistiftgebiet, 1985-2000, edited by the meticulous decipherers Bernard Echte and Werner Morlang. So here was a real trouvaille: sometime even before 1924 or 1925, Walser had begun to pencil, on the backs of calendars, on blank spaces offered by rejection slips, telegrams, bank statements, and other sorts of used stationery, an immense reserve of stories, feuilletons, sketches, improvisations, from which to extract, at will, fair copies.”

(It’s possible, one thinks, that items—often writing-saturated—gather’d in places like the Prinzhorn-Collection, or the Musée de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, be codify’d awaiting decipherment.)

Walser: “It can so happen that, for example, horses are unduly put to work, because they cannot speak and thus cannot be asked. They are unable to negotiate. No horse can be asked for its opinion, for nature has denied it the ability to pronounce one. It is altogether disgusting the way human beings do not refuse such delicacies as frogs’ legs . . .” Beginning to spiral off into a consideration of war, with the line “who smiles a fine snaky rhetoric out of his mouth,” and eventually ending with the sentence: “With prayer it is certainly not a matter of succeeding, or accomplishing something useful, but first and foremost of its being beautiful.”

~

Guffaw’d at midnight, reading about Lethem’s nerd white boys, Arthur Lomb and Dylan Ebdus. Arthur, the nerdier, trying to talk the talk: “‘Man, that one guy was trying to act real scary, but I could see his face, he looked like a baby, his lips were all blubbery. Yo, I probly could of taken him if you hadn’t come out just then. Lucky for him I’d say, yo.’ Arthur’s careful slurring of certain words, in contrast to his sharply nerdish pronunciation elsewhere, is wincingly obvious to Dylan, who wonders why Mingus doesn’t just smack him upside the head and command him to stop . . . Arthur turns to Dylan instead. ‘What you think, we could of taken them, yo?’

‘Don’t yo me,’ said Dylan.”