Charles Burchfield

Struck by something the Dark Clover put down here—comparing the rather banal mass-consumption one summer of a few reels of retrograde celluloid (Star Wars) to what he sees as “a mass political action” (the recent French “riots”). That nobody registers oneself as participant in history (or in “a singular historic event cycle”)—(that’s, apparently, left to trans-Atlantic instructors like himself). That’s not what struck me, though. What did is how exactly Clover’s report of the “summer of Star Wars” compares with Jonathan Lethem’s in The Disappointment Artist, (though I think he,—being a novelist, viddy’d it some ghastly number like twenty-one showings—against Clover’s mere “six or seven”). For the record, I think I caught parts of it some years later, telly’d.~

Pound (Guide to Kulchur): “Does any really good mind ever ‘get a kick’ out of studying stuff that has been put into water-tight compartments and hermetically sealed?”

I accept the hokey dialogue only if everything they say is correct (Under the Volcano):

“The Mayas,” he read aloud, “were far advanced in observational astronomy. But they did not suspect a Copernican system . . .” “Why should they? . . . What I like though are the ‘vague’ years of the old Mayans. And their ‘pseudo years,’ mustn’t overlook them! And their delicious names for the months. Pop. Uo. Zip. Zotz. Tzec. Xul. Yaxkin.”And Consul Geoffrey Firmin, inebriated, saying “cheerfully and soberly in passing,” to “the little public scribe . . . crashing away on a giant typewriter”:

“Mac,” Yvonne was laughing. “Isn’t there one called Mac?”

“There’s Yax and Zac. And Uayeb: I like that one most of all, the month that only lasts five days.’’

“In receipt of yours dated Zip the first!—”

“But where does it all get you in the end?”

”I am taking the only way out, semicolon . . . Goodbye, full stop. Change of paragraph, change of chapter, change of worlds—”~

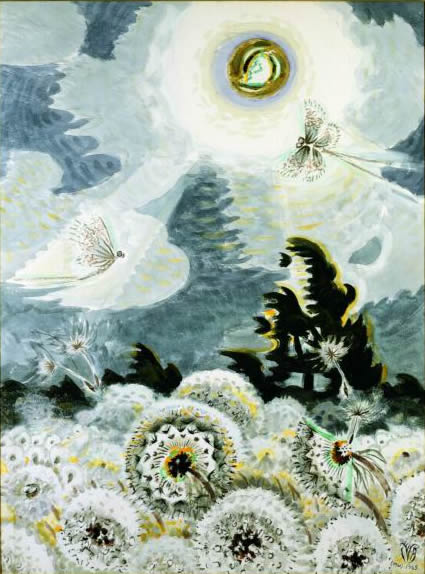

How Samuel Palmer’s early paintings rhyme with Charles Burchfield’s (1893-1967):

Charles Burchfield, Cottage in the Trees, (1955, watercolor)

Palmer in a letter to George Richmond (Shoreham, 1828), trailing off into lines by Milton:Forgive my spirits they sometimes haunt the caves of melancholy; ofttimes are bound in the dungeon, ofttimes in the darkness; when the chain is snapt they rush upward and revel in the temerity of their flight. What I have whisper’d in your ears I should not blaze to vulgar apprehensions: if my aspirations are very high, my depressions are very deep, yet my pinions never loved the middle air; yea I will surrender to be shut up among the dead, or in the prison of the deep, so I may sometimes bound upward; pierce the clouds; and look over the doors of bliss, and behold there ‘each blissful deity, How he beneath the thunderous throne doth lie’.

Samuel Palmer’s “Early Morning” (1825, pen and ink and wash, mixed with gum arabic, varnished)

And, against all savage meekness, against all mean means, against all topiary’d fine erectings, Palmer’s note on excess (1825):Excess is the essential vivifying spirit, vital spark, embalming spice . . . of the finest art. Be ever saying to yourself ‘Labour after the excess of excellence.’ . . . There are many mediums in the means—none, O! not a jot, not a shadow of a jot, in the end of great art.