“Life flows in staccato pieces belonging to different systems.

Only our clothing, not the body, joins together the disparate moments of life.”

Viktor Shklovsky,

A Sentimental Journey

“. . . others said that the twentieth century began when it was discovered that people come from apes and some people said they were less related to apes because they had developed more quickly. Then people started comparing languages and speculating about who had the most advanced language and who had moved furthest along the path of civilization. The majority thought it was the French because all sorts of interesting things happened in France and the French knew how to converse and used conjunctives and the pluperfect conditional and smiled at women seductively and women danced the cancan and painters invented impressions. But the Germans said that genuine civilization had to be simple and close to the people and that they had invented Romanticism and lots of German poets had written about love, and about the valleys where there lay mists. The Germans said they were the natural upholders of European civilization because they knew how to make war and carry on trade, and also to organize convivial entertainments. And they said the French were vain and the English were haughty and the Slavs did not have a proper language and language is the soul of a nation and Slavs did not need any nation or state because it would only confuse them.”

~

“Internet users represented a new type of citizen, which they called a hypercitizen. The hypercitizen was the first supranational and totally free citizen in history and anyone could become one if they managed to stop thinking the old way and started to think differently, because in the coming world order, labor and capital and raw materials would no longer play any role. And parliamentary democracy would give way to hypercivic democracy and each hypercitizen would be equal to every other hypercitizen and everyone would live interactively. And every week one language and 35,000 hectares of forest expired on average. And 96% of the world’s population spoke 240 languages, while 4% spoke 5,821 languages and 51 languages were spoken by only one person. And in 1996, the United Nations launched a program called UNIVERSAL NETWORK LANGUAGE, and many Anarchists studied Esperanto and in 1910 a handbook was published in Esperanto explaining how to assassinate political leaders.”

Patrik Ouředník, trans. Gerald Turner,

Europeana: a Brief History of the Twentieth Century (Dalkey Archive, 2005)

~

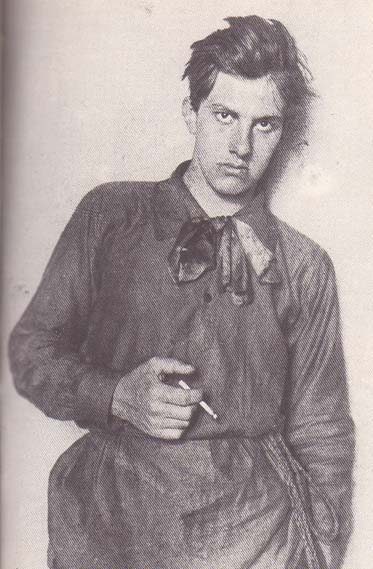

Ouředník in an

interview: “Is it possible to express a period of time, a specific historical time, without using traditional narrative means, however direct or allusive they are, such as a historical novel or an intimist narrative? To find a form that would enable the narrator—like History itself—to be terribly banal, while pretending to be original.”

And: “Of course, we would like to get rid of this stupid century. However, I don’t think that people have decided to do so.

In any case, my goal was not to conceive of the twentieth century as a theme—not even in the sense of a “reflection theme”—but as a literary figure. The primary question wasn’t to know what events, what episodes were characteristic of the twentieth century, but which syntax, which rhetoric, which expressiveness belonged to it, in what sense was it redundant, etc.

I could simplify this: what were the key words of the twentieth century? Undoubtedly,

haste (rather than “chaos,” which is no more appropriate to the twentieth century than to any another). This meant, let’s try to write a hurried text. Another peculiarity of the twentieth century, I think, is

infantilism—with everything that it implies, from the romantic-commercial image of juvenility to the refusal of taking the full responsibility of one’s acts and words. Let’s try then to write a childish text, a text that could have been told by a kid reciting his lesson or by the village idiot. Thirdly, this century has been explicitly scientific. This meant, let’s use a vocabulary more or less scientific, with all its contradictions and, if possible, with all its vacuity. These are the elements that gave birth to the form and content of the book.”

~

Missing: catalpas, Carmen, correspondances.